Philippe Defrance, a renowned chef, restaurant-owner and prolific journalist on topics that highlighted the presence of France and the French in Australia, was born on February 28, 1925 at Le Meux in the department of the Oise in France. His father, Louis Defrance, was a sheep-farmer and trader. We do not know anything about his mother apart from her maiden name Marthe Becker and that she was born in 1905. In later life, and in particular in relation to his restaurant activities, Philippe would adapt the family surname to ‘de France’. He attended the College de Compiègne (now the Lycée Pierre d’Ailly) in 1937-1938, followed by two years of additional study in Compiègne and then was evacuated to Bayeux where he attended the École Létot. Philippe was employed as a baker in Compiègne, before enrolling in the National School for Cattle Husbandry (École nationale d’élevage bovin), graduating in 1944.

Philippe Defrance, a renowned chef, restaurant-owner and prolific journalist on topics that highlighted the presence of France and the French in Australia, was born on February 28, 1925 at Le Meux in the department of the Oise in France. His father, Louis Defrance, was a sheep-farmer and trader. We do not know anything about his mother apart from her maiden name Marthe Becker and that she was born in 1905. In later life, and in particular in relation to his restaurant activities, Philippe would adapt the family surname to ‘de France’. He attended the College de Compiègne (now the Lycée Pierre d’Ailly) in 1937-1938, followed by two years of additional study in Compiègne and then was evacuated to Bayeux where he attended the École Létot. Philippe was employed as a baker in Compiègne, before enrolling in the National School for Cattle Husbandry (École nationale d’élevage bovin), graduating in 1944.

In 1945 he married Georgette Barbero-Vacin and they had two children, Thierry and Jérôme. Defrance worked in various capacities primarily in the meat industry before leaving France in 1966 for California, where he worked as an apprentice chef in a French restaurant in Los Angeles. He and his first wife divorced in 1967. He applied for a position as an ambulance driver in Vietnam with the American Red Cross, but was not successful. So, still in search of adventure, he arrived in Australia in 1967, where he worked first as a cook in Sydney and Tumut before working as a labourer on the Snowy Mountains project. The following year he went to Victoria and worked as a cook at Mt Buller and in Melbourne for the next few years.

In 1970, he took a job as a senior cook on the island of Bougainville in the then Australian colony of Papua New Guinea. He subsequently moved to Singapore, where he was chef de cuisine in a large hotel restaurant.

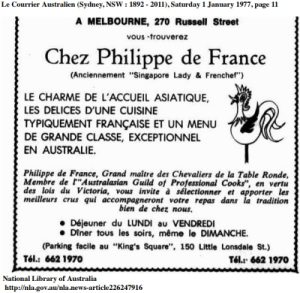

Defrance returned to Melbourne in 1972 with his Singaporean wife, Goh Poh Lung, whom he had married in 1972 and with whom he had one child, Richard, who was born in 1974. He decided to open his own restaurant, which he initially called ‘Singapore Lady and the Frenchef’, renaming it in 1975 as ‘Chez Philippe de France’. For the next sixteen years he ran the restaurant and through it provided work, accommodation, food and advice to some 500 young French people who came to Melbourne in search of adventure, just as he had done. Whether he employed non-French people is not known. The restaurant promised diners, as the advertisement in the image that accompanies this entry shows, an ‘Asiatic welcome and a typically high-class French cuisine, exceptional in Australia’.

In 1988, Defrance decided it was time to hang up his chef’s hat. His health was beginning to be a problem, and indeed the following year he returned to France for major cardiac surgery. On returning to Australia, probably in 1992, he no longer worked as a chef but maintained a busy schedule of activity.

Defrance had always been interested in journalism. In France he had written for various professional magazines relating to the sheep and meat industries. From his early days in Australia he had published articles in Le Courrier Australien, often under the pseudonym of Frank Phillip. In 1993, he set up Éditions Francaustralia, and launched a quarterly publication which he called Le Melbournal, Le Journal de Melbourne, Ville de Jeanne d’Arc, taking his inspiration from the statue of Joan of Arc in front of the State Library of Victoria. Four issues of this journal were produced. Full of puns, jokes and personal anecdotes, his writing reflects his character as a slightly risqué bon vivant. He celebrated friends and colleagues in poetry and song; he paid homage to the famous Belgian singer-composer Jacques Brel on his death in 1978; he wrote about little known French explorers and about the restoration of the tomb of Comte Lionel de Chabrillan, the first consul of France in Melbourne. Defrance did not shy away from taking on the issue of Australian and New Zealand opposition to French nuclear testing in the Pacific, within the context of a fait divers about a twenty-three-year-old French girl who was attacked by a New Zealander and ended up in hospital in Melbourne. He questioned why the New Zealander received a positive hearing from the police and the Australian press, when the French girl clearly was in no way responsible for the actions of the French Ministry of Defence. Throughout this period, Defrance continued to write his regular column ‘Pel-mel’Bourne’ for Le Courrier Australien, reporting on events in Melbourne of interest to the French community and commenting on current issues.

In 1993, Defrance organised the first dinner of the Victorian branch of the Académie Culinaire de France, to celebrate his own election as a member of the Académie and that of John Miller, head of the Food Department at William Angliss College in Melbourne. Members of the Académie enjoy national prestige in France and play an important ambassadorial role for the French culinary arts and pastry professions. Defrance went on to organise a further fourteen dinners for the group over the next four years in different restaurants in Melbourne.

Many of the dinners he organised provided occasions to honour new members of the Académie. During his time as head of the Académie Culinaire de France in Victoria, membership had grown to thirteen, all of whom had been approved by the Paris office of the organisation, as well as four associate members. Defrance received a number of honours for his work from the French government, and private and public organisations. In 1982, he was awarded the Diploma of Honour of the Chaîne des Rôtisseurs de France, an international gastronomic society founded in Paris in 1950. In 1985, he was appointed a member of the Melbourne Tourism Authority. Three years later, Defrance was made a Chevalier in the Ordre du Mérite Agricole for services to sheep-raising and active involvement in the participation of 250 Australian sheep-breeders and growers in the bicentenary celebrations of the Bergerie Nationale de Rambouillet, a prestigious agricultural research and educational facility near Paris, renowned for its genetic database and breeding program for merino sheep. In November 1995, one of the dinners Defrance organised for the Victorian branch of the Académie Culinaire de France celebrated his own promotion to the rank of Officer in the same French order, in recognition of his services to French gastronomy.

Defrance was a great sportsman: he had been a boxer in his youth as well as a swimmer and water polo player. He loved horse-racing and many of the dinners of the Académie Culinaire were organised to coincide with the eve of the Melbourne Cup.

Philippe Defrance died on April 27, 1998. His obituary in Le Courrier Australien of May 10 described him as a committed republican, un maître queux (master chef), un bon vivant and lover of the good things in life, an author and storyteller, and someone known by all for his kindness. He asked that the following characteristically witty death notice be published.

He was cremated, according to his wishes, without ceremony, just like the dogs that he loved so much. His ashes were scattered on the track at Moonee Valley. Thus in his after-life he will be able to enjoy crottin, his favourite cheese and the urine of young foals will replace the Sancerre. The atheist rejoins the nothingness of absolute truth and universal justice. Only when you drink a fine champagne or a Condrieu or a Côte Rôtie, can you toast his memory. That way you won’t think too often of him.

Philippe Defrance was a larger than life character who was an active member of the French community in Melbourne for thirty years. His small restaurant was the location of many celebrations and parties bringing together the chefs of many of the French restaurants in the city. It was listed amongst the fifty best restaurants in Melbourne at the time of the 150th anniversary of Victoria in 1985. The restaurant presented a limited menu so that it would be manageable in a small kitchen but offered to Melburnians the very best of traditional French cuisine. Quenelles and terrines featured, along with truffled omelette, Pâté de Caneton en Croûte à l’Armagnac à l’Orange, for which the recipe survives, and rack of lamb when spring lamb was available. In spite of his journalism, Defrance did not extend his presence via television, he was not a media personality the way many chefs have become in more recent years. Nor did he publish a book of his recipes. Nonetheless, his contribution as an extremely active member of the French community, his establishment of a branch of the Académie Culinaire in Melbourne and his promotion of exchanges between sheep breeders in Australia and France make him a person worthy of recognition.

Image: Le Courrier Australien, July 1, 1977, p. 11.

Author: Jane Gilmour, Melbourne, July 2023.

References

Le Journal de Melbourne, No. 1, January 1993, No. 2, April 1993, No. 3, July 1993 and No. 4, November 1993 (private collection).

Le Courrier Australien, articles by ‘Pel-mel’Bourne’ from mid 1992 to March 1996.

Académie Culinaire de France Australia, www.academieculinairedefrance.com/index.php?

La Bergerie Nationale de Rambouillet, www.bergerie-nationale.educagri.fr/.

Le Courrier Australien, ‘Nécrologie, Philippe de France’, May 10, 1998, p. 3.

John Miller, www.lestoquesblanches.com.au.

Keywords

French restaurants Melbourne; sheep-raising; journalism; Académie Culinaire de France.

NOTE: ISFAR holds some scanned material relating to his life, including two scrapbooks and the four issues of Le Journal de Melbourne. We are willing to make this available to interested and authorised parties.