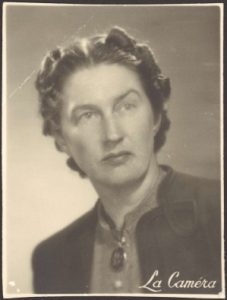

Christina Ellen Stead, born in Sydney on 17 July 1902, was an Australian novelist, short story writer, journalist and translator. Her fictional works, often bitingly parodic and politically astute, increasingly reflected her Marxist leanings, honed over forty-two years of writing, and her affiliations with sympathetic left-wing institutes. Her two Paris-centred novels, The Beauties and Furies (1936) and House of All Nations (1938), stamped with personal opinion and political insight, remain weighty critiques of the historic and social upheavals of 1930s France and Europe.

Spurred by an unhappy childhood that was marred by the death of her mother in 1904, a domineering father, poverty and two successive stepmothers she disliked, Stead left Australia in 1928 to forge an independent life. But the memories of the past lingered and inspired two of her most acclaimed novels: Seven Poor Men of Sydney (1934) and The Man Who Loved Children (1940). By then she was practising what she called ‘the novel of strife’ in which characters in conflict are variously the victims of social injustice, human frailty, unwise moral choices and the unkindness of fate.

Following her arrival in London in 1928, Stead joined a company of grain merchants where she met and fell in love with William Blake (formerly Wilhelm Blech), a brilliant economist, broker, novelist and journalist. In 1929 they moved to Paris where she took up a secretarial post and Blake a senior administrative position in the company’s American Travelers’ Bank. Their affair heralded a lifelong partnership and an itinerant lifestyle as they moved between Europe and America while establishing themselves as cosmopolitan authors. All Stead’s twelve novels relate to places in which she lived, observed and fictionally judged. Verbally brilliant, intellectually sharp, digressive and psychologically profound, they make demands on the reader, but they cast penetrating light on moments in history that changed both society at large and individuals caught up in its flux.

In 1929 Stead and Blake moved to Paris where they resided until 1935. There, opportunely, Stead’s secretarial position in the Travelers Bank gave her inside knowledge of the vagaries of the 1930s financial world, triggered by the 1929 Wall Street Crash and the economic calamities it unleashed. Largely set in a fictitious bank when France was in reality in the throes of stock market volatility, the privations of the Great Depression and the threat of Hitler’s escalating might, House of All Nations offers on a broad canvas a damning assessment of the capitalist system and, via its cavalcade of characters, the nature of speculatory frenzy and the corrupt human responses it generates. Most of those who work for the novel’s bank are opportunists, profiteers and egotists: wily managers, scheming middlemen, manipulative agents and ruthless arrivistes, who dupe the unwary investor, cheat the gullible client and reap the monetary benefits. For Stead they are the exemplars of those the Marxist theorist castigates: the affluent minority who exploit the poor and the working class to further their own status, social advantage and wealth. As the book unfolds, Stead broadens her scope: the ‘house of all nations’ represents the crumbling political and financial edifices of European nations at risk. In its closing chapters she traces the demise of the major players and the bank’s inexorable and ultimate collapse, even as, in parallel, Europe floundered in the grip of oppressive leaders, economic instability and unstable governments. Stead’s invented scenarios were thus not unlike those she witnessed at the time. The outbreak of the Second War in 1939 would plunge ‘all nations’ into crisis, shattering the false utopias of the 1930s to which so many had unguardedly clung.

In The Beauties and Furies, as in House of All Nations, Stead takes the heedlessness of the 1930s unremittingly to task: its characters – acquisitive, self-serving, profligate – belong to a world of human unconcern and predatoriness. Yet the novel is less a critique of an era’s capitalist bodies than a scathing portrait of post-war and post-Crash social types. The male protagonist, a pretentious, shallow student, who is in Paris to advance his research, proves as intellectually expedient as he is fickle in his amorous entanglements. This is particularly the case with his English lover, a bored housewife, come abroad to seek pleasure until the novelty of foreign surroundings and the excitement of a romantic fling wear off. Stead draws on the clichéd perception of Paris as the city of glamour and promiscuousness to expose the folly of her protagonists as they pursue false ideals and an illusory happiness. There is a common ideological edge to Stead’s fictional works. The Beauties and Furies is, in essence, a study of class. Her male and female protagonists are smug bourgeois. One is committed to self-advancement; the other unready to forego her home with its chattels and material comforts. The Paris venture, it transpires, is a failure; the travellers remain unchanged by their experience.

Stead’s role in left-wing organisations complemented her ideologically driven literary output. In 1935 in Paris, while Fascist Germany was burning books deemed degenerate, she attended the First International Congress of Writers for the Defence of Culture, an anti-fascist writers’ lobby that included literary notables such as André Gide, Louis Aragon and André Malraux. In her role as the delegation’s unofficial British secretary, she recorded the event’s political thrust: how best to address the deficiencies of the capitalist paradigm and resist the emerging menace of Europe’s dictatorships. Yet, Stead was never a propagandist or proletarian writer like the group’s predominantly communist participants; rather her leftist leanings encouraged her to denounce all forms of hypocrisy, injustice and dishonesty in all political arenas. In the rich ferment of 1930s events and ideologies, she remained open-minded and judiciously evaluated the impact of theorists like Darwin, Nietzsche and Freud. Again, although she never identified as a feminist, successive novels explored the patriarchal hegemony and the nature of feminine passions, ambitions, travails and regrets. This was acknowledged, if tardily, in the 1980s when London’s Virago Press reissued those of her novels that most representatively critiqued the contemporary feminine lot.

In 1935 and 1936 Stead and Blake travelled between Europe, England and the United States. In July 1937, they re-embarked for America. There, they contributed articles to the communist weekly journal New Masses. At the same time, they branched out: in 1938 Stead was reviewing Australian novels for the New York Times Book Review. Between 1942 and 1943 both she and Blake worked as screenwriters for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in Hollywood, as well as co-editing the anthology Modern Women in Love: Sixty Twentieth-Century Masterpieces of Fiction. In 1946, fearful of burgeoning American anti-communist sentiment, they returned to a peripatetic life in Europe. This period was marked by a flurry of literary works, although Stead’s true success as an author eluded her until late in life. In 1947 they resettled in England, living in considerable poverty despite Blake’s role as a researcher and scripter for a German film studio and the relative success of his works. In 1952 they married, Blake having finally secured a divorce from his first wife. Upon his death in 1968 Stead took up a short-term visiting fellowship at the Australian National University in Canberra; it encouraged her to return to Australia in 1974 where she remained until her death in Sydney on 31 March 1983.

Literary success in Australia came late for Stead, largely because she was perceived as an expatriate writer of cosmopolitan works, some of which, moreover, were judged obscene. However, increased fame abroad and the US republication in 1967 of The Man Who Loved Children kindled recognition in her homeland. In 1974 she was the recipient of the inaugural Patrick White Literary Award, bestowed for the lifetime achievement of older writers. Posthumous fame followed, notably with the publications of Ocean of Story: The Uncollected Stories of Christina Stead in 1985 and I’m Dying Laughing: The Humourist (1986). In their wake, translations of her works into numerous languages continue to broaden her repute. In 1988 The Man Who Loved Children was published in France as L’Homme qui aimait les enfants, and in 2018 The Beauties and Furies appeared as Splendeurs et fureurs.

Image

Christina Stead, ca. 1938

C.S. Daley photograph collection

National Gallery of Australia, nla.obj-144459442

Author

Rosemary Lancaster, University of Western Australia, September 2021.

References

Ackland, Michael, Christina Stead and the Socialist Heritage, New York, Cambria Press, 2016

Geering, R. G. (ed.), new edition, Christina Stead, A Web of Friendship: Selected Letters, 1928–1973, Melbourne, Miegunyah Press, 2017 (first published 1992)

Geering, R. G. (ed)., Christina Stead, Talking into the Typewriter: Selected Letters, 1973–1983, Melbourne, Miegunyah Press, 2018 (first published 1992)

Gribble, Diane, Christina Stead, Oxford University Press, 1994

Lancaster, Rosemary, ‘All That Glitters: Illusory Worlds in Christina Stead’s The Beauties and Furies (1936) and House of All Nations (1938)’, in Je Suis Australienne: Remarkable Women in France, 1880–1945, 2008, pp. 124–150

Lidoff, Joan, Christina Stead, New York, Frederick Ungar Publishing Company, 1982

Rowley, Hazel, Christina Stead: A Biography, rev. ed., Melbourne, Miegunyah Press, 2007 (first published 1993)

Rowley, Hazel, ‘Politics and Literature in the Radical Years, 1935–1942’, Meridian, vol. 8, no. 2, 1989, pp. 149-159

Keywords

Christina Stead, writer, Paris, 1930s, Marxism, Sydney